Lost Property of Felbridge, Pt 2 - East side of the north end of Imberhorne Lane

As we steadily advance through the 21st century and with an extensively accrued Felbridge archive, it is perhaps time to reflect on the lost property of Felbridge, dwellings and structures that have disappeared, some in the lifetime of former and current Felbridge residents and some properties whose mere existence has only become known through researching old documents and maps relating to Felbridge and its surrounding area.

This document is the second in a series that aims to catalogue these lost properties and, where known, give a few details about the property and the cause of its loss. Some of the lost properties we have covered before and have their own handout devoted solely to their history, in which case only a brief synopsis will be supplied here along with any additional information discovered since the publication of the original handout. Research into other lost properties may produce enough information to create a future handout devoted solely to that property and other lost properties will inevitably prove to have very little surviving information on them, but at least they will have been identified and included in this series of catalogued lost property of Felbridge. No doubt some lost property will escape our attention altogether or not yet have been revealed through our researches and there are many more recent properties that have been sacrificed for the numerous housing developments in Felbridge and the surrounding area of the late 20th and early 21st centuries; this latter category of properties will not be covered in detail unless the lost property was of significant merit.

The lost property covered will be presented by location within the Felbridge area made up of the land holdings of the Evelyn estate of the late 1700’s that incorporated the manor of Hedgecourt and their own Felbridge lands (for further information see Handout, The Early History of Hedgecourt, JIC/SJC 11/11) with additions made by the Gatty family after their purchase of the estate in 1856 (for further information see Handout, Charles Henry Gatty, SJC 11/03); the ecclesiastical parish of Felbridge created in 1865 out of parts of the ecclesiastical parishes of Godstone, Horne and Tandridge in Surrey and East Grinstead and Worth in Sussex (for further information see Handout, St John the Divine, Felbridge, SJC 07/02i); and the Civil Parish of Felbridge created in 1953 (for further information see Handout, Civil Parish of Felbridge, SJC 03/03]; together with the occasional lost property abutting these areas as part of manorial lands associated with Felbridge. In all, an area stretching from the Newchapel area in the north across to the Snowhill and Crawleys Down area in the west, the north end of East Grinstead Common, North End and Imberhorne manor and its associated holdings in the south and Chartham and the Wiremill area in the east.

Part 1 of this series covered the area of Felbridge that encompassed the west side of the north end of East Grinstead Common, including Halsford and western side of North End, starting at Yaxley Cottages and finishing at 42, North End. Further family details relating to the properties in this document can be found in an additional appendix available on request or on line as Additional Family Appendix to Lost Property of Felbridge, Pt. 1, at www.felbridge.org.uk

This document, the second in the series, will catalogue and, where possible, provide the history of the lost property of the east side of the north end of Imberhorne Lane. Further family details relating to the properties in this document can be found in an additional appendix available on request or on line as Additional Family Appendix to Lost Property of Felbridge, Pt. 2, at www.felbridge.org.uk

East side of the north end of Imberhorne Lane

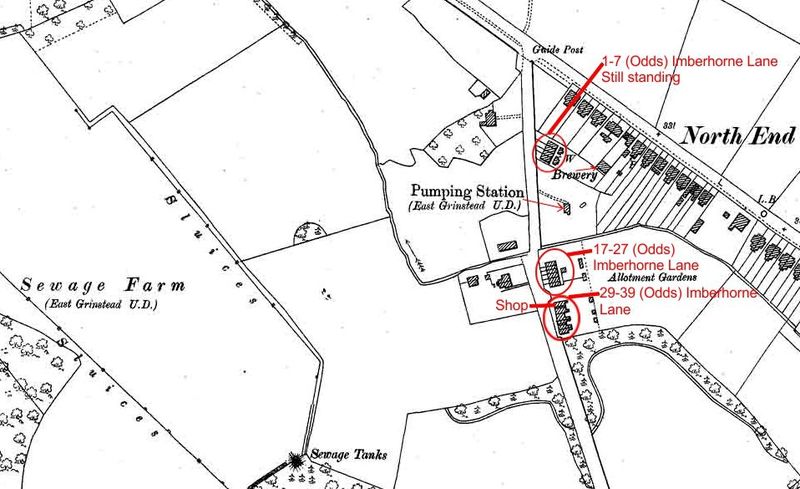

This area extends south from the site of the offices of Knighthood Corporate Assurance, along the east side of Imberhorne Lane, past the terrace of four old cottages (nos.1, 3, 5 & 7, Imberhorne Lane) still standing, and up to and including the two blocks of maisonettes (nos. 17- 47, Imberhorne Lane [odd numbers only]). Sixteen lost properties and one public lime kiln have been identified as once being situated in this area.

In 1871, the first property on the east side of the north end of what was then called Imberhorne Road was occupied by stone mason Thomas Jupp [for further information see Handout, Biographies from the Churchyard of St John the Divine, Pt.3, SJC 09/06]. Thomas Jupp and his family had moved there sometime between 1861 and 1871 from Woodlands Cottages, situated on the west side of the main London road at North End [for further information see Handout, Lost Property of Felbridge, Pt.1, JIC/SJC 07/18]. The dwelling in Imberhorne Road was situated somewhere between the north end of the road and a run of dwellings described in the 1871 census as ‘shop and no.1 unoccupied’ followed by nos.2-6, Imberhorne Road (see below). The 1873 O/S map shows a single building set back from the road, south of the stream on the east side of Imberhorne Lane (TQ 3763 3924). This appears to be within the same plot of land as the first row of dwellings (17-27 odd numbers only). This dwelling was not there in 1861 and had gone by 1881, by which date Thomas Jupp and his family had moved to Glen Vue in East Grinstead.

Tin Hut(TQ 3761 3929)

Known locally as the ‘Tin Hut’, this once stood between the row of cottages now numbered 1, 3, 5 & 7, Imberhorne Lane (formerly 1-4, Imberhorne Lane) and the North End Pumping Station (see below), now the site of the Long Stay car park. The hut had once functioned as the East Grinstead Medical Centre for school clinics and was relocated from its original site in Railway Approach, on the corner of the junction with Brooklands Way, to the site in Imberhorne Lane at the beginning of World War II. Little has been documented about the hut other than it may potentially have been relocated for use by the Red Cross in the event of war related emergencies or incidents, or for use by members of the local Air Raid Patrol (ARP), or possibly both. The hut was a single storey structure, with corrugated steel walls under a gabled roof of corrugated steel. It was positioned gable-end on to Imberhorne Lane, with a finial on the rear gable and an air-raid siren on the front gable, which, even after the end of the war, was tested regularly well into the 1960’s. There was a single storey, open-sided structure at the rear of the hut and, at some time prior to 1962, a single storey extension had been attached to the south side of the building.

In the late 1950’s and early 1960’s, the Tin Hut served as a garage, rented from the local council by the cosmetic factory Kolmar that was situated a short distance to the south on the west side of Imberhorne Lane, in which to store their delivery lorry. The structure last appeared on the 1960 O/S map and had gone by the early 1970’s.

The Bungalow

In 1953, the East Grinstead Directory lists a dwelling called ‘The Bungalow’ occupied by Dora Roper, situated between the last of the terrace of four cottages (1, 3, 5 & 7, Imberhorne Lane) and the first of the terrace of six cottages adjacent to the North End Pumping Station on its south side. As the Directory only lists dwellings, this would place The Bungalow in the vicinity of the Tin Hut and North End Pumping Station. The 1955 O/S map depicts a small cluster of structures in this position that can definitely be identified as the Tin Hut and the open-sided structure at the rear, the North End Pumping Station (see below) and a small rectangular structure between the two. This small structure is on the site of what is today a small brick building that was built as a telephone exchange to support the National Grid back-up control centre for the area that once stood on the site opposite, on the west side of Imberhorne Lane, known locally as ‘Das Bunker’ (further information follows in Lost Property of Felbridge, Pt. 3).

Dora Roper, the listed resident of The Bungalow, was born Dora Harriett Reed in Slaugham, Sussex, on 5th January 1890, the daughter of James and Emma Reed. In 1911 Dora was working in Thames Ditton as a servant and in 1915 married Reginald Roper in East Grinstead. Dora and Reginald had at two daughters, Elizabeth Florence born in 1919 and Nancy Mary born in 1925, both born in Devon. By 1939, Dora, Reginald and Nancy had moved to North End where Reginald Roper ran the North End Club until his death in 1946, [for further information see Handout, Eating and Drinking establishments of Felbridge, Part I, SJC 05/07]. In 1946 Dora and their daughter Nancy took over the Club which they continued to run until about 1949, probably moving to The Bungalow around this date. It is not known how long Dora lived at The Bungalow, but had moved from the area when she died in 1967.

Unfortunately, no other information has yet been found relating to The Bungalow. However, a possible theory for The Bungalow is that when the Tin Hut ceased its war time function it was turned into a dwelling for a brief period of time before being rented to the Kolmar cosmetic factory.

North End Pumping Station(TQ 3763 3927)

The pumping station was built on waste land, on part of the demesne of Imberhorne manor on the east side of Imberhorne Lane, on what is now the site of the Imberhorne Long Stay car park. There is very little information about the early days of the pumping station but it is generally believed to have been built to deal with the increasing problem of the disposal of sewage from a rapidly expanding community in the last quarter of the 19th century.

The disposal of sewage and waste from dwellings in the East Grinstead area had come to a head by the mid 19th century as Wallace H Hills takes up the story in his book The History of East Grinstead, published in 1906:

The universal use of cesspools in East Grinstead was abandoned very many years ago, but the drainage system adopted was an extremely crude and dangerous one. At the centre of the town there was a brick drain on each side of the road, receiving both surface water and sewage. These drains united in one sewer, which emptied itself into the Swan Mead, irrigating this large meadow, which was close to the town and extended from the present Police Station in West Street, across Queen's Road and Glen Vue to the Railway Hotel. It then flowed towards a pond, the outfall passed into an open ditch, which in course of time also received drainage from cottages in Glen Vue, two or three pigstyes, the occasional overflow of the Workhouse cesspools and the irrigation from a field near the present Cemetery, over which a drain taking the sewage from the houses in Chapel Lane, now West Street, emptied itself. This accumulation found its way along the stream and entered the Medway at OldMillBridge. Another drain commenced at the back of the Church, passed through Brewer's or Brewhouse Lane, and emptied itself on to a field near the Hermitage. A third commenced in the garden at the back of the Swan, receiving the sewage from several houses in that neighbourhood. This was carried to a cesspool built in an old stone pit at the back of Chapel Lane and the overflow passed into a cleft in the rocks and disappeared. The Rocks district at the north entrance of the town was drained by another sewer emptying into the Deane cherry garden. The Railway sewage and that from a dozen houses near the old station was taken along the line towards Tunbridge Wells until it ultimately disappeared in a cleft in the rocks. There were three other minor sections, all equally primitive and dangerous. Each person disposed of his refuse just as it seemed him best, without reference to any law save that of gravitation.

Things had got so bad by 1853 that on October 27th of that year Mr. C. R. Duplex was appointed Nuisance Inspector, but he was unable to do anything. The first Sewage Authority for the town was appointed on September 18th, 1866, but this also was able to do very little. On June 25th, 1875, a Parochial Committee, consisting of Messrs. W. V. K. Stenning (the first public office he ever held), C. Absalom and T. Cramp, were appointed to act in conjunction with the Board of Guardians in carrying out a drainage system for the town, which was by this time in a fearful condition. The hollow in the fork formed by the junction of Ship and West Streets was nothing but a large pond of reeking sewage; the whole of the Swan Mead, where Queen's Road and Glen Vue now stand, was merely a receptacle for filth; while on the other side of the town the Moat fields were in almost as bad a condition and typhoid fever was rampant. The Committee first endeavoured to get land for a sewage farm in the valley between East Grinstead and Forest Row, but the opposition was so powerful that they were compelled to look elsewhere, and eventually the present site of 30 acres in the parish of Lingfield was purchased. Five loans, altogether amounting to £13,000, were raised during 1879, and necessary extensions caused a further expenditure of £2,630 before the end of 1882. The pumping engine was fixed in May, 1879, and the bulk of the connections were made with the farm during 1880. The broad irrigation system of treatment was continued most efficiently until 1903, when the bacteria system was introduced with even more satisfactory results.

From the description given by Hills, and the fact that W V K [William Vicesimus Knox] Stenning lived at Halsford, formerly part of East Grinstead Common, it would seem likely that the North End Pumping Station in Imberhorne Lane was constructed to prevent the developing area at the north end of the Common and North End from replicating what had or was happening in the town of East Grinstead.

The North End Pumping Station was built by the East Grinstead Urban District Council (EGUDC) in 1887 to pump sewage from rapidly expanding North End to a Sewage Farm on the west side of Imberhorne Lane (now the far side of the of The Birches Industrial Estate). As already established, the Pumping Station was built on wasteland, being part of the demesne of the manor of Imberhorne and the Sewage Farm was also situated on another piece of land owned by the manor of Imberhorne that the EGUDC had leased from Sir Edward Blount for fourteen years in 1887. The Sewage Farm consisted of a brick-built sewage tank (TQ3745 3908), into which the sewage was pumped by the North End Pumping Station. Extending from the sewage tank was a series of sluices to disperse the sewage down the field. In 1892, it was proposed that the North End Sewage Pumping Station be expanded to ‘drain’ what was described as the ‘Sackville estate’ between North End and the town [East Grinstead]. It was deemed that the engines at the North End Pumping Station were ‘quite capable of doing double the amount of work’ and therefore adequate for the proposed extension. In 1901, it was reported that the EGUDC decided to provide a duplicate engine and pumps at the North End Pumping Station and in 1902 it was reported that the sum of £1,500 was loaned by the Local Government Board, to be repaid over 40 years, ‘for the purpose of carrying on the North End Scheme’. The Board also sanctioned ‘the appropriation of the necessary ground at the North End pumping station’, although the committee decided to ‘defer the scheme for consideration by the Council’. However, from map evidence, the North End Pumping Station had doubled in size by 1910, presumably as a result of reaching an agreement to accommodate the extra engine and pumps.

The North End Pumping Station of living memory was built as a typical municipal-style Victorian red-brick structure under a slate roof. It was a tall, single-storey building and rectangular in shape. From memory and photographs, it had two tall arched windows with contrasting brickwork either side of a large central door; the long side facing Imberhorne Lane, being set back from the road by about 10ft (3m). It always struck me as fairly light inside the building when playing in it as a child so it probably had more windows, either in the end or back walls. Map evidence indicates that there was a ‘tank’ depicted at the rear of the building, which implies that there was a low structure (wall) that could be seen above ground with the bulk of the tank set below ground level. In June 1940, it was reported in the local newspapers that the ‘large engine at North End Pumping Station’ was in need of repairs and it was agreed to accept the tender of £104 8s made by ‘Messr. Frank Pearn Co Ltd of West Gorton, Manchester’ for the ‘provision of spare parts’. A local resident of Imberhorne Lane from the 1940’s recalls that the North End Pumping Station housed what he called a stationary steam engine and that the ‘flywheel made a high pitched, ringing tone’ that could be heard as far away as the main London road (A22).

In 1956, the EGUDC invited tenders from ‘experienced contractors’ to complete a series of works at the sewage at the North End and Eden Vale Sewage Disposal Works, which included:

a) The construction of about 1,400 yards of temporary 9 inch diameter spun iron pumping main, the major portion of which will be laid above ground.

b) Alterations at the North End Pumping Station.

c) The construction of earth sludge lagoons at Eden Vale Sewage Disposal Works and other remedial works.

Shortly after this date, the North End Pumping Station went out of use.

During its life as a pumping station, and possibly for a short time after it ceased operating, (as witnessed by a former local resident who lived opposite the site) ‘the old pumping station used to be a good haunt for the old men of the road [tramps], who used to get in there because it was nice and warm at night. There was always someone on duty and the old pot would be going for a cup of tea.’ Later, after being vandalised and having all its windows smashed (culprits unknown and before my time), the North End Pumping Station proved to be a huge magnet as a local play area for the children from this end of Imberhorne Lane, many forbidden by their parents to go anywhere near the old pumping station. Entry was gained through one of the smashed windows and we would all meet up inside. I remember that when the sun shone through the window openings, intricate patterns formed on the floor, which would suggest that the framing was still intact. By the mid 1960’s the building had been completely gutted except for a few tubular handrails, frequently used by us to sit on as the floor was carpeted with broken glass shards. Outside, the surrounding site had become over-grown with vegetation, which proved to be a haven for flying insects and butterflies that would flit amongst the weeds and grasses on warm summer days.

After standing derelict for many years the old pumping station was demolished in the late 1960’s and eventually turned into the Imberhorne Long Stay car park.

Public Lime Kiln(TQ 3771 3920)

The only reference of a public lime kiln at North End is to be found in The History of East Grinstead by Wallace H Hills who wrote in 1906:

The Common, already referred to, commenced just beyond the White Lion Hotel and, but for a few isolated cottages, formed a wild open tract reaching practically from the town to Felbridge and from Baldwins Hill to Imberhorne. The Duke of Dorset, as Lord of the Manor, began its enclosure about 1760 and his successors continued it until the only public piece now remaining is the Lingfield Road Recreation Ground. At North End formerly stood the public lime-kilns. Farmers used to fetch chalk by road from Lewes and make their own lime, for agricultural purposes, in the kilns on the Common. These were used by whoever needed them and, as may be imagined, disputes in regard to their occupation were not rare. The cartage of chalk was so great and so necessary an industry that by many general and local Acts carts conveying it were exempted from the payment of tolls, but a special clause was inserted in the last Act governing the East Grinstead roads (1850), withdrawing this exemption in regard to chalk and lime continuing it in regard to lime only when being conveyed for use in improving land.

Unfortunately no further collaborating documents have yet surfaced regarding public lime kilns at North End and sadly Wallace Hills does not reveal his sources but it is unlike him not to have had some evidence to support his claim (for further information on lime kilns in the Felbridge area see Handout, Lime Kilns & Lime Burning in Felbridge, SJC 11/00). However, the 6” O/S map of 1873 does show a circular feature in the rear garden of the cottage within what are now the allotments (plot 13A) which could have been the site of the lime kiln. It should be pointed out that if the public lime kiln had existed in this vicinity as recorded by Hills, it would probably have ceased operating prior to 1873 as that particular series of O/S maps tended to label lime kilns that were in operation.

17, 19, 21, 23, 25, 27, 29, 31, 33, 35, 37 & 39, Imberhorne Lane (aka 1-12, Imberhorne Lane) (Row 1: TQ 3762 3923, Row 2: TQ 3763 3919)

This was a row of cottages, in two blocks, that stood on the plot of land (now the site of two blocks of maisonettes, nos. 17-47, Imberhorne Lane [odd numbers only]), adjacent and south of the North End Pumping Station. Map evidence dating to 1873 depicts a row six terraced cottages, then a gap with a track leading to the ‘Allotment Gardens’ at the rear of the properties, followed by a pair of semi-detached cottages with a passageway between each at ground level and an abutting further terrace of four cottages with a passageway between the second and third dwelling at ground level. From photographic evidence dating to the 1920’s the northern half of the pair of semi-detached properties had the appearance of a shop with large ground floor ‘shop window’.

These cottages were built on land that was once part of the demesne of Imberhorne manor and were numbered by 1911 and re-numbered by 1928. For the early part of their life they were known simply as Imberhorne Road (later Imberhorne Lane) Cottages but in 1911, they were numbered 1-12, Imberhorne Lane. The 1911 numbering was a bit confusing, as a second row of four terraced cottages (1-4, Imberhorne Lane, still standing and now numbered 1, 3, 5 & 7, Imberhorne Lane) had been built sometime between 1879 and 1891, and the first four cottages of the terrace of six further north in Imberhorne Lane were also numbered 1-4, Imberhorne Lane, thus for a period of time, two sets of dwellings numbered 1-4, Imberhorne Lane coexisted. Eventually all the cottages on the east side of the north end of Imberhorne Lane were renumbered and the most recent terrace of four became nos.1-7, Imberhorne Lane [odd numbers only] and the original developments consisting of the terrace of six cottages, the semi-detached property (including the shop premises) and the terrace of four cottages became nos.17-39, Imberhorne Lane [odd numbers only]. To reduce confusion, nos.17-39 [odd numbers only] will be used throughout the following text to identify which property is under discussion.

Returning to the lost property of 17-39, Imberhorne Lane [odd numbers only], the pair of semi-detached cottages with the shop (later numbered 29 & 31, Imberhorne Lane) and the southern-most terrace of four cottages (later numbered 33, 35, 37 & 39), were constructed between 1861 and 1871. From the 1871 census, the shop and dwelling in the northern half of the pair of semi-detached properties was unoccupied but the dwelling in the southern half and the terrace of four were occupied. From census and map evidence, the terrace of six cottages (later numbered 17, 19, 21, 25 & 27) were constructed between 1871 and 1873 and were fully occupied by 1881.

In September 1888, the ‘twelve freehold cottages’, together with a piece of building land with ‘a frontage of 24ft (7.31m) and a depth of 100ft (30.48m)’, was put up for auction. The cottages were described as: ‘brick-built and slated dwelling houses, situate in Imberhorne Lane, East Grinstead; eleven of the houses containing four rooms, and one containing five rooms and a cellar [the shop]. …… The drainage is carried into the public sewer, and they are supplied with the company’s water. The whole let to good tenants, and producing a yearly rental of £94 18s’.

The building land appears to have sold (although the site has not yet been established) but the cottages failed to sell and were put up for auction again in October 1889. At this auction they were described as:

Sale of TWELVE EXCELLENT FREEHOLD COTTAGES affording a capital opportunity for securing a sound and lucrative investment.

Messrs. Langridge and Freeman

Will sell at AUCTION, at the Crown Hotel, Edenbridge, on Monday, October 14th 1889, at Two o’clock, in One or Three Lots, twelve capital well-built FREEHOLD COTTAGES, situate at North End, Imberhorne Lane, East Grinstead. All let to an exceedingly punctual paying tenantry at very low weekly rentals, producing an annual gross income of £94 18s, but estimated to be well worth £110 10s per annum. The houses are substantially constructed, are well drained, and water is laid on.

However, it was reported on 19th October 1889, that the twelve cottages still did not sell, but that they could now be ‘treated for privately with the auctioneers upon very advantageous terms’. As a point of interest, mains water may have been laid on but initially only to an outdoor stand pipe to each individual cottage and although waste water may have been ‘well drained’, toilet facilities were in the form of shared ECs [earth closets]. Unfortunately it has yet been possible to determine who put the cottages up for sale or when the cottages were sold although by the 1940’s they were all in the ownership of one George Brooker but sadly no further information has yet been established about him.

Using photographs dating to between the mid 1920’s and mid 1950’s, map evidence and personal memories of former residents it has been possible to establish the construction techniques, materials and styles for these twelve ‘well built’ dwellings, which in their latter years, were known as 17-39, Imberhorne Lane [odd numbers only].

17, 19, 21, 23, 25 & 27, Imberhorne Lane

From early photographs, the terrace of six cottages was built of Flemish bond brickwork under a slate roof. The brickwork had different coloured headers and stretchers that gave a patterned effect, suggesting reasonable quality bricks were used. The headers were pale in colour and the stretchers were darker. There was a large central chimney stack between each pair of properties (nos.17&19, 21&23 and 25&27). Each stack had an over sailing head, with six flues but no pots. Windows on the front were 6 over 6 sash (without horns) set into slightly arched lintels of soldier bricks with pre-cast sills and the front doors were 4-panel doors, typical of the mid-Victorian era. The arrangement of doors and windows on the front of the terrace consisted of mirrored pairs; starting with the front door and a window on the ground floor with one window above the ground floor window for no.17, which was mirrored for no.19. Thus nos. 21&23 and nos.25&27 were their mirror image.

Outside no.17, a gas lamp-post stood on the grass verge, the only one on this stretch of Imberhorne Lane. A picket fence ran along the top of a bank on the terrace side of the grass verge with a gate at no.17, a shared gate for nos. 19&21 and nos.23&25 and a fourth gate at no.27. Each gate was accessed via a set of brick steps cut into the bank leading to a brick path and the gates and paths at each end probably served as the communal passages to the rear of the properties.

Unfortunately, there are no good images of the rear of the properties to discuss their appearance. However, from map evidence, this terrace of six cottages did not have an outshoot at the rear, each dwelling being rectangular in shape, containing two rooms on the ground floor with two above. There was, however, what appears to be a communal wash-house behind the central pair of dwellings. This would have been shared by all six households and was indicative of the period. There appears to two ECs at the rear of the ‘back garden’, adjacent to the boundary with the ‘AllotmentGardens’. However, by the mid 1920’s, the dwellings were likely to have been fitted with water closets as a photograph shows a soil vent-pipe at the rear of the properties. Early mapping suggests that the ‘back garden’ may also have been a communal space as there were no visible divisions depicted. There were, however, hedges dividing the front garden plots. Also, as a point of interest, the 1920’s photograph depicts an enamel sign on the front wall, to the left of the door of n.17. The sign was advertising Dixon’s, pertinent as Oliver Bull, the son of William Bull who was resident in no.17, was working at Dixon’s ‘Mineral Water Factory’, from the brewery premises at 32 & 33, North End.

29 & 31, Imberhorne Lane

This property was built as a shop and dwelling at no.29 and second dwelling at no.31 and the purpose built shop is known to have had a cellar beneath it. From early photographs, the front of the building was rendered but the side and back walls were exposed brickwork, under a slate roof. The brickwork appears to be very poor quality, which by the middle of the 1920’s was already showing signs of spalling (the effect caused when water enters porous bricks and they begin to break down). The line of the flue was clearly visible on the side wall where smoke from the fire has bled through and darkened the brickwork, again confirming that the bricks were of poor quality. Two photographs of the rear of the building potentially shows that the back wall was lime washed. There was a 2-stack chimney at each end of the property. Both stacks had plain heads and pots with two flues, suggesting that four rooms were heated. The left-hand side of the property had a large 12-light shop window under a timber hood upon which the name of the shop could be displayed. Right of the window was the shop door with a normal size window set centrally on the first floor. Adjacent to the shop door was an arched passage-way leading from front to back with a ‘blind’ window set above it on the first floor. To the right of the passage-way was the front door for the second dwelling (no.31) with a ground floor window to its right and a centrally set window on the first floor. The inclusion of the ‘blind’ window suggests that the dwellings were of equal size on the first floor.

Like the terrace of six cottages, 29 & 31, Imberhorne Lane were also built higher than the level of the road, slightly out of alignment to the terraces on either side and further forward. A picket fence ran along the top of a bank on the dwelling’s side of the grass verge but unfortunately there is no clear view of the gate or gates positions, although there would, no doubt, have been brick steps leading up to a paved path.

From map evidence, 29 & 31, Imberhorne Lane were each rectangular in shape, but were wider and slightly longer than any of the cottages in the terraces of six or four. No.29 would have had the front room as the purpose built shop and the dwelling unit would have been one room on the ground floor with potentially three above, whilst no.31, would have been two rooms on the ground floor and two above. At the rear of the property there was a projection, half the width of each dwelling, which is indicative of a single storey wash-house. These were set at each end of the dwellings to allow for the passage-way between the two dwellings. Map evidence dating to 1873, shows just one EC at the rear of the ‘back garden’, adjacent to the boundary with the ‘Allotment Gardens’ implying that it was a shared facility with the terrace of four (33, 35, 37, & 39, Imberhorne Lane). However, by 1895 the one EC has been replaced with three separate ECs, one for every pair of dwellings (three structures but probably separate facilities). Like the row of six terraces, early mapping suggests that the ‘back garden’ may also have been a communal space as there were no visible divisions depicted. There were, however, hedges in the front garden plots, although there is no good image to determine the divisions.

33, 35, 37, & 39, Imberhorne Lane

Again, from early photographs, the front of the terrace was rendered but the side and back walls were exposed brickwork, under a slate roof. From map evidence, the terrace abutted no.31, as there is no evident gap between the two structures, although the terrace of four was built on the same alignment as the terrace of six, thus further back from the road than nos.29 and 31. The visible brickwork on the end wall shows that the bricks are of a consistent colour and give the impression that they were of reasonable quality and well laid. There were two chimney stacks in front and behind the ridge, on the party walls between nos.33 & 35 and 37 & 39. The stacks had plain heads and pots with two flues per stack, which would indicate that only two rooms in each dwelling were heated. The front elevation shows that each pair of dwellings was a mirror image, thus no.33 had a door to the left and window to the right on the ground floor and a window above on the first floor, whilst no. 35 was reversed. However, between nos. 35 and 37, there was a passage-way giving communal access to the rear. Above the passage way was a window suggesting nos. 35 or 37 may have had an un-equal division on the first floor. The front elevation of the first two cottages was repeated for nos.37 and 39.

By 1895, map evidence indicates that cottages had a back to back projection, approximately half the width of each property, this would be indicative of a single storey wash-house each. Also, by this date, each pair of the terrace of four were sharing an EC at the rear of the ‘back garden’, adjacent to the boundary with the ‘AllotmentGardens’. Also, like the row of six terraces and nos.29 & 31, early mapping suggests that the ‘back garden’ may also have been a communal space as there were no visible divisions depicted.

Unfortunately there is no clear image of the front of the terrace of four, although they had a picket fence and appear to have had one gate per pair of cottages and again, being set higher than the road, were accessed by brick steps.

The families of 17, 19, 21, 23, 25, 27, 29, 31, 33, 35, 37 & 39, Imberhorne Lane and their interconnected community

By 1871, only six of the twelve cottages that had been built on the east side of Imberhorne Road, south of the North End Pumping Station, and of these only five were occupied, no.29, the southern half of the pair of semi-detached properties containing the purpose-built shop and a dwelling was recorded as unoccupied. The census records that the majority of the male heads of household were working in the building trade: John Vines (31, Imberhorne Lane) and John Vigar (39, Imberhorne Lane) were working as carpenters; George Skinner (37, Imberhorne Lane) was as a bricklayer; and George Buckland [also recorded as Bish] (35, Imberhorne Lane) was as a labourer. The only male head of house not working in the building trade was George Wheeler (33, Imberhorne Lane) who was working as an agricultural labourer.

By 1881, all twelve dwellings on the east side of Imberhorne Road, on the south side of the North End Pumping Station, had been completed and were fully occupied. From the census records, there are again several male heads of household working in the building trade, along with several of their sons and boarders/lodgers: John Harding (17, Imberhorne Lane) and John Barlow (39, Imberhorne Lane) were working as carpenters; and Charles T Andrews, son of Thomas Andrews (25, Imberhorne Lane) was a bricklayer’s labourer. Labourers included: George Buckland (23, Imberhorne Lane); David Brown (27, Imberhorne Lane); John Waldock and his step-son Leonard Phelps (29, Imberhorne Lane) with lodgers John Giles, William Bunsdy and John Shepperd; Henry Smith (31, Imberhorne Lane), together with second head of household George Rackley; Thomas Blackstone and his half brother William Gibb jnr. (37, Imberhorne Lane); and Horace Pentecost (39, Imberhorne Lane). The 1881 census also reveals a fairly large number of agricultural or farm labourers including: brothers James, Peter and John Harding (17, Imberhorne Lane); father and three sons, Henry, George, Henry jnr. and Thomas Stone (19, Imberhorne Lane); William Barfield (35, Imberhorne Lane) with lodgers William Buckland sen., William Buckland jnr. and Thomas Ridgely; and William Gibb sen. (37, Imberhorne Lane). There was also one blacksmith, William Watkins (33, Imberhorne Lane). A possible reason for why so many of the residents were working in the building trade was be the development of North End, which saw the re-building of several of the old dwellings and the construction of a large number new buildings along the west side of the London road between 1879 and 1895 [for further information see Handout, Lost Property of Felbridge, Pt.1, JIC/SJC 07/18].

Interestingly there is no mention of a shop keeper living in the row of cottages in Imberhorne Lane so it is possible that the property was not functioning as a shop in 1881, especially as there were two round the corner at North End by this date. Another point of interest is that 21, Imberhorne Lane was in the occupation of single woman Jane Gold, living on her own in the property and working as a haberdasher, although she had formerly been the School Mistress at Saint Hill School, East Grinstead. The census records that a large proportion of the residents of the cottages were born and bred in East Grinstead but there were also quite a few interlopers who had moved to the area from places such as Bristol, Buckinghamshire, Cambridgeshire, Cornwall, Dorset, Gloucestershire, Leicestershire, Northamptonshire, Somerset and Wales. Also, of the original five households of 1871, only one, George Buckland and his family, were still living there, although, for reasons unknown, they had moved from 35 to 23, Imberhorne Lane; the other four households had moved on.

The 1891 census still reflects a significant proportion of male residents working in the building trade, including Frank Godley (19, Imberhorne Lane) who was a plumber. As a point of interest, Frank was the father of Sidney Godley who received the Victoria Cross for his actions during World War I [for further information see Handout, Pte. Sidney Godley VC, SC 03/00]. It is also interesting to note that none of the residents recorded as living in the cottages in 1881 were still in residence in 1891 and a more diverse range of male occupations was beginning to creep in, including: Harry Aylward (17, Imberhorne Lane) who was working as a carman; William Stripp (31, Imberhorne Lane) who was working as a drayman (probably for the brewery round the corner at 32-32 North End [for further information see Handouts, Eating and Drinking Establishments, Pt. 1 SJC 05/07 and Lost Property of Felbridge, Pt.1, JIC/SJC 07/18]; and Albert Pentecost (39, Imberhorne Lane) who was working as a baker’s assistant, probably for the bakery also round the corner at 31, North End. Of the other male residents, if they were not working in the building trade they were domestic gardeners. Working women included: Eliza Hewett (33, Imberhorne Lane) and Emily Pentecost (39, Imberhorne Lane), both working as charwomen and Martha Webber (23, Imberhorne Lane), Jane Stripp (31, Imberhorne Lane), Rebecca Kilner (33, Imberhorne Lane) and Martha Heasman (39, Imberhorne Lane) all working as female domestic or general servants.

The type of occupations recorded in the 1891 census reflects three local factors. Firstly the continued development of North End and the requirement of a workforce allied to the building trade; secondly the growth and establishment of local businesses such as the brewery and bakery at North End; and thirdly the growing need for domestic and general staff and gardeners, for the developing estate of Imberhorne after its purchase by Edward Blount in 1878. Again a large proportion of the residents of the cottages were born and bred in East Grinstead but there were still a few interlopers who had moved to the area either from neighbouring villages such as Ardingly, Chiddingstone, Fletching, Hartfield, Horsham, Lingfield, Redhill, Reigate and West Hoathly, or from further afield, such as Brockham in Surrey, Hampshire, Huntingdonshire and Suffolk. It is also interesting to note that all of the families were new to the cottages; there was not one single household that had been living there in 1881.

In 1901, the occupational trend of working in the building trade was still evident with brothers Arthur, John and William, sons of George Bonny (21, Imberhorne Lane) who were brick makers; George Bull (17, Imberhorne Lane), Charles Adams (23, Imberhorne Lane) and Charles Baldwin (27, Imberhorne Lane) who were general labourers; brothers Charles and William, sons of Eliza Hewett (33, Imberhorne Lane) who were respectively a bricklayer and bricklayer’s labourer; and Arthur, son of Emily Pentecost (39, Imberhorne Lane) who was a builder’s carter. Several male residents worked in timber, including: William, son of Mary Ann Webber (19, Imberhorne Lane) and Albert Pentecost (23, Imberhorne Lane) who were sawyers; Horace, son of Emily Pentecost (39, Imberhorne Lane) who was a timber yard labourer, probably for the Stenning Timber Yard in East Grinstead; and there was even a ‘wood brick maker’, James Ranger (35, Imberhorne Lane). There were now only three males that probably worked for the Blounts of Imberhorne, Alfred Webber (25, Imberhorne Lane) who was a domestic gardener; Thomas Creasey (29, Imberhorne Lane) who was a farm timber carter; and Thomas Coomber (37, Imberhorne Lane) who was an agricultural labourer. The decline in the number of agricultural workers and the absence of any domestic and general staff living in the cottages was due to the fact that the Blounts had set about a building programme of cottages specifically to house their workforce, either at Imberhorne Farm, Imberhorne Gardens (now known as Chapman’s Lane) or at North End. There were, however, a couple of new occupations listed for the male residents, Albert son of Mary Ann Webber (19, Imberhorne Lane) was working as a shop assistant, probably in one of the two shops on North End, one at no.17 and the other at no.21, or possibly in the purpose-built shop at 29, Imberhorne Lane; and Henry Pelling, boarding with George Bonny (21, Imberhorne Lane), who was an office boy. As for the female residents, widowed head of house Mary Ann Webber (19, Imberhorne Lane) and Emma Gibb, sister-in-law of widowed Charles Adams (27, Imberhorne Lane), were both listed as housekeeper; no other women declared an occupation at the time of the census.

In 1901, four of the households that had been in residence in 1891 were still there: Mary Ann Webber (19, Imberhorne Lane) widow of Alfred Webber, although she had moved from 23, Imberhorne Lane; and Charles Adams (27, Imberhorne Lane), Eliza Hewett (33, Imberhorne Lane) and Emily Pentecost (39, Imberhorne Lane) who were still in the same properties as 1891. The majority of the new residents had been born in East Grinstead or the local area, except James Ranger and his wife Mary Ann (35, Imberhorne Lane) who respectively came from Tunbridge Wells, Kent, and Clandon, Surrey, although their children were all born in East Grinstead.

The 1911 census reveals that there were still a few men living in the cottages with connections to the building trade, particularly bricklayers including: William, son of William Bonny (21, Imberhorne Lane) and Charles Hewitt (29, Imberhorne Lane) who were bricklayers; and Walter Mason (27, Imberhorne Lane) who was listed as a bricklayer, builder. However, occupations were becoming more diverse. There were two road men who worked for the Urban District Council, William Bull (17, Imberhorne Lane) and Thomas Coomber (37, Imberhorne Lane)); two men worked with wood or at the timber yard: Albert Pentecost (23, Imberhorne Lane) and Fredrick Pentecost (39, Imberhorne Lane); there were still several domestic gardeners George Bonny and his grandson Ernest Butcher (21, Imberhorne Lane) and Abraham Brooker (35, Imberhorne Lane). Two unusual occupations included: Oliver Bull (17, Imberhorne Lane) who was working in the mineral water factory, operating from the site of the brewery round the corner at 32-33, North End that had been established by George Bonny between 1871 and 1881, and George Wright (25, Imberhorne Lane) who was a partially sighted hawker. Working women included: Lily, daughter of Mary Ann Webber (19, Imberhorne Lane) who was a housemaid (daily work); Ellen and Caroline Creasey, grand-daughters of Eliza Hewett (33, Imberhorne Lane) who were respectively working as a laundry maid and dressmaker, and Martha, the wife of Frederick Pentecost (39, Imberhorne Lane) who was a charwoman.

It is interesting to note that 17-39, Imberhorne Lane [odd numbers only] did eventually become home to some very long-stay residents. George Buckland and his family occupied 23, Imberhorne Lane from its construction until sometime between 1881 and 1891. Alfred Webber succeeded George Buckland at no.23 and is recorded as occupying the dwelling in 1891. Sadly Alfred Webber died in 1893 and after his death his widow Mary Ann, daughter Lily and grandson Frederick Alston Webber moved to 19, Imberhorne Lane, where Mary Ann continued to live until her death in 1911, and in 1901 Mary Ann’s son Alfred C Webber had moved with his family to 25, Imberhorne Lane, although he had left by 1911.

George Bonny and his family occupied 21, Imberhorne Lane from sometime between 1891 and 1901. George died at no.21 in 1927 and his wife Esther died from the cottage in 1952 when their son William took over the property. William Bonny and his family are potentially the last family to reside at no.21, as he was listed as living there in 1953 and the properties were demolished circa 1958/59 having stood empty for a short period of time. Other long-stay residents include: Walter Mason and his family who moved into 27, Imberhorne Lane sometime between 1901 and 1911, succeeding Charles Adams who had been living at the property since sometime between 1881 and 1891. Walter remained there until his death in 1938 and his wife Mabel stayed there until her death, the property being taken over by their son Dennis who was living there in 1953 and, like William Bonny, may potentially have been the last resident to occupy the property before its demolition.

Another long-stay resident was Emily Pentecost, a widowed charwoman and her family who moved into 39, Imberhorne Lane, sometime between 1881 and 1891. By 1901, Emily’s son Albert Pentecost had moved into 23, Imberhorne Lane and remained there until sometime between 1916 and 1928. Emily remained at 23, Imberhorne Lane until her death in 1908 when her grandson Frederick Pentecost took over the property. Frederick remained at the property until sometime between 1928 and 1939 when Martha Heasman (the daughter of Emily Pentecost and Frederick’s aunt) took over from him. Martha remained at the property until sometime between 1945 and 1953. Albert Pentecost, one of Emily’s sons, moved to 33, Imberhorne Lane sometime between 1891 and 1901 and lived there until sometime between 1911 and 1928. Thomas Coomber and his family took up residence at 37, Imberhorne Lane sometime between 1891 and 1901, remaining at the property until sometime between 1916 and 1928. However, in 1928, Thomas’s son Leonard Coomber was living at 23, Imberhorne Lane where he was to remain until his death in 1946 and his wife Florence until her death in 1949.

The Hewett/Hewitt family

Of all above mentioned families, the Hewett/Hewitt family probably had the longest connections with the cottages on the east side of Imberhorne Lane. The first in a long line of Hewitts to live there was Eliza Hewett, who moved into 33, Imberhorne Lane sometime between 1886 and 1891, succeeding her nephew Richard Marden who had moved to the property sometime between 1881 and 1886. However, Eliza’s family connection goes back to when the cottages were first built in 1871, when George Skinner and his family moved into 37, Imberhorne Lane, as George Skinner was Eliza’s brother-in-law, having married her sister Hannah, as his first wife, in 1848. Also, in 1881, John Harding and his family were living at 17, Imberhorne Lane and his son John married Eliza’s daughter Eliza Kilner in 1882.

Eliza Hewett had been born in East Grinstead in 1840, the daughter of Henry Marden and his wife Sarah Ann née Skinner, although some census records put Eliza’s birth year as 1841 or 1842. The Marden family home was Thatched Cottage (further information follows in Lost Property of Felbridge, Pt. 3), on the west side of Imberhorne Lane until the death of Henry in 1885. Eliza married Henry Kilner in 1862 with whom she had Eliza born in 1862. In 1866, Eliza had Mary Rebecca Kilner, two years after the death of Henry Kilner, and later the same year Eliza married Henry Hewett in East Grinstead. Eliza's family was completed with Elizabeth Hewett born in 1868, Charles John Hewett born in 1871 and William James Hewett born in 1878, all three born in East Grinstead.

In 1891, the Hewett household at 33, Imberhorne Lane, consisted of: Eliza, recorded as married, the head of the house and working as a charwoman; Rebecca Kilner, her 25-year old single daughter, working as a domestic servant; sons Charles Hewitt aged 19, working as a bricklayer’s labourer and William Hewitt aged 12, a scholar; along with grandchildren: Alice Kilner aged 5, Florence and Thomas Creasey aged 3 and 1 respectively (three of Eliza’s daughter Mary’s children, one outside marriage and two with Thomas Creasey). In 1901, the Hewett household consisted of Eliza, head of household, and living with her were two grand-daughters, Ellen and Caroline Creasey, daughter of Eliza’s daughter Mary and her husband Thomas Creasey who in 1901 were living at 29, Imberhorne Lane. Eliza continued to live at 33, Imberhorne Lane until just before her death in 1915.

At some point during her occupation of 33, Imberhorne Lane, Eliza ran a small shop from the premises of 29, Imberhorne Lane (the purpose-built shop), that went by the name ‘E. Hewett Confectioner, Tobacconist &c’. The most likely time for this venture would have been whilst her daughter Mary and son-in-law Thomas Creasey were in residence, during the late 1890’s and early 1900’s. Family members recall that Eliza sold home-made sweets, ginger beer and tobacco related products. Interestingly Eliza is never recorded as a shop keeper in any of the census records. One of her great grand-daughters comments that ‘Sadly no-one is left to tell us about Granny Hewett’s Recipes. Nothing was written down, not even in my Granny’s old Mrs Beeton’s Cookbook blank pages. The only recollections came from oral stories my mother passed on to me and they are sparse. One such is that Granny H sold home-made toffee in broken pieces. It was very hard! said Mum. She also made her own lemonade and ginger beer’. The original shop sign [spelt Hewett, although today the family goes by the spelling Hewitt] still survives, retained by another descendant of the family.

Sometime between 1908 and 1911, Eliza’s son Charles Hewitt moved from the Baldwin’s Hill area of East Grinstead to 29, Imberhorne Lane, taking over the property from his half-sister Mary and her husband Thomas Creasey and their family. Charles had married Isabella Ellen Bradford in 1903; Isabella had been born at Parish Cottage (now called Crofters) in East Park Lane, Newchapel, Horne, Surrey, in 1881. In 1911, Charles was listed as a bricklayer and the Hewitt family consisted of Violet Clara born in 1905, Grace Helen, known as Gracie, born in 1907 and Olive May, known as Tom, born in 1908. Charles and Isabella would go on to have Ansley Edith born in 1911, Charles James Valentine born in 1913 (sadly he died of meningitis in 1920), Doris Isabel Mary born in 1915 and Barbara Sybil Marden born in 1926. Charles Hewitt spent all his life working as a bricklayer until failing sight prevented him from working. Eventually he and Isabella moved to Holtye Rise in East Grinstead, a development of pre-fabricated dwellings, before moving to Woodlands Road, East Grinstead, and 29, Imberhorne Lane was taken over by their son-in-law Albert Harnblow, who had married their youngest daughter Barbara, in 1950.

As a point of interest, Olive, Charles and Isabella Hewitt’s third daughter, penned several memories about her childhood growing up at 29, Imberhorne Lane, which give some idea of the dwellings and what life was like at the turn of the 20th century in the Imberhorne Lane area. Olive, known as Tom, was born in 1908 so her memories of the Imberhorne Lane area must date from around 1912/13 to the early 1920’s when she moved to work in Brighton. She writes:

Our road was a long country one, just tarred in the centre, grass verges and ditches, little traffic except horses and carts….. We also had, in the lane outside, one street lamp. It was a gas lamp that I often climbed up and turned off to help the man who was supposed to do it every morning….. Dad never said he was going to the end of the lane, but always it was ‘up to the waypost’, otherwise called the sign post.

We lived in a house with cellars underneath and a passage to one side and a vacant plot on the other…. It contained a lot of doors, not very well-fitting and when the winds roared, the carpets waved up and down like waves on the sea…. For cold nights, patchwork bedcovers, lined with an old blanket or curtain, were needed as our house was very cold. On winter nights, Mum used to put bricks to warm in our fire oven. When we went to bed these were first wrapped in brown paper and wrapped again in pieces of cloth or cloth bags and put into our beds to warm them.

Mum made jams, pickles and wine all to store for the winter or hard times when Dad could not work because of rain or snow. Builders could not work then and they did not get paid, so we were very glad Mum and Dad had saved food for bad days, when money was very scarce.

During hard times, the cook at the Manor House was allowed to sell dripping which we loved on toast or baked potatoes and if you took a large jug or milk can, it was filled with thick tasty soup which could be diluted quite a lot and helped many families provide for their children in times of unemployment. When it rained or we had snow or hard frosts, many of the men on buildings etc, could not work and there was no unemployment money as there is today.

We very rarely asked ‘what can I do?’ and I do not remember ever hearing the words ‘I am bored’. My mother would soon find us a job, cutting blocks of salt to fill salt jars or the soap into blocks. It came in large bars, Primrose yellow, Carbolic and a weird looking one white with bits of green, brown and yellow, useful for scrubbing floors….. We cleaned knives with emery powder and whitened the front steps with hearthstone.

Mum worked very hard as all water had to be brought in to the house – and, when finished with, taken out again. The lavatory was at the top of the garden grown over with roses, honey-suckle and most things that would climb. At night, before we washed for bed, Dad would collect all of us who needed to use the lavatory (or ‘Little House’ as we called it) and, with a lantern for dark nights, escort us up the path to the Little House at the top end of the garden.

There were two small shops and a Baker…. One shop sold anything from bacon to candle and oil for lamps, soap etc and I always remember the mixed smells of this shop. The other one sold sweets and we could take our farthings and half pennies in and get eight aniseed balls or a strap of toffee for one farthing, sweets like this were not wrapped and you were given them in a screw of paper….. Sometimes we would take cakes (for neighbours) or meat and potatoes to the Bakers who cooked them, after the bread came out of the oven, some people only had open fires with no ovens. Bakers charged 2d and we usually got one penny to take and collect them and the Baker sometimes gave me odd pieces of new bread or cakes that had broken off in baking.

Writing many years later and from memory, Olive’s daughter Janet and nephew John Deane (son of her sister Doris Hewitt) penned their memories of the Hewitt’s life at 29, Imberhorne Lane, after the purpose-built shop had been incorporated as part of the dwelling. The shop area contained Charles Hewitt’s bed, as he now slept on the ground floor due to failing or failed sight. The only other furniture in the room was a chest of drawers, a cupboard and chair beside the fire. Rag rugs were placed beside the bed and in front of the fire. The former shop door functioned as the front door and to try and keep out the drafts, it was hung with a curtain. Half-way down the outside passage there was another door that led into the entrance hallway with stairs leading to the first floor, under which were situated stairs leading to the cellar. Either side of the entrance hall was a door into the original shop (then Charles Hewitt’s bedroom) and a door into the main living room. This room was heated by a range on which the Hewitt’s also cooked. Either side of the range stood a chair, one for Charles and the other for Isabella Hewitt. A large table took up most of the space in the centre of the room with a dresser against the southern wall, next to an old grandfather clock. Leading off the living room was a second door leading to the cellar stairs and a third door, in the rear wall, to the scullery/wash-house area.

From photographic evidence, the scullery/wash-house area had been extended by the time the Hewitt’s had made the property their home and included not only the original stone sink and boiler (copper) of the wash house, but also a butler’s sink and gas stove, but still no running water. In order to extend the scullery/wash-house area the original back door had been partially blocked-up and the original rear 6 over 6 pane sash window of the ground floor had been re-sited to the position of the top section of the original doorway, allowing the original window area to be broken through as a doorway into the extended scullery/wash-house. A new 8-pane casement widow had then been set into the extended section of the scullery/wash-house, above the gas stove and butler’s sink. Bath time consisted of a tin bath in front of the fire, all the water having to be brought into the house from a cold tap mounted on a stake at the rear of the property. The cold water then had to be heated to the required temperature and then baled out afterwards. This arrangement was still in place until at least the early 1950’s when Charles and Isabella left the premises, and this was probably still the case until the property’s demolition.

The final years of 17, 19, 21, 23, 25, 27, 29, 31, 33, 35, 37 & 39, Imberhorne Lane

During the years of World War II, all the cottages on the east side of the north end of Imberhorne Lane suffered some form of damage, mostly classed as ‘slight’ or ‘medium’, no direct hits fortunately. The War Damage Reports highlight just how many of the men were absent, no doubt serving in the war, as nearly all the claims record a female head of household. The Reports, dating to 1944 and 1945, also list that the owner of the properties was George Brooker, thus all the residents of 17-39, Imberhorne Lane [odd numbers only] were tenants of his.

The following, from the War Damage Reports, shows the names of the tenants and the extent of damage sustained by the properties during Word War II:

|

Owner |

Address |

Resident |

Date |

Damage |

Cause |

|

George Brooker |

19, Imberhorne Lane |

Mrs Skinner |

23/06/1944 |

Slight |

|

|

|

North End Pumping Station |

|

25/03/1945 |

Slight |

P.P. |

|

George Brooker |

17, Imberhorne Lane |

Mrs Bull |

25/03/1945 |

Slight |

P.P. |

|

George Brooker |

19, Imberhorne Lane |

Mrs Skinner |

25/03/1945 |

Slight |

P.P. |

|

George Brooker |

21, Imberhorne Lane |

W Bennett |

25/03/1945 |

Slight |

P.P. |

|

George Brooker |

23, Imberhorne Lane |

Mrs Coomber |

25/03/1945 |

Slight |

P.P. |

|

George Brooker |

25, Imberhorne Lane |

Mrs Chart |

25/03/1945 |

Slight |

P.P. |

|

George Brooker |

27, Imberhorne Lane |

Mrs Mason |

25/03/1945 |

Slight |

P.P. |

|

George Brooker |

29, Imberhorne Lane |

C Hewitt |

25/03/1945 |

Medium |

P.P. |

|

George Brooker |

31, Imberhorne Lane |

C Baldwin |

25/03/1945 |

Slight |

P.P. |

|

George Brooker |

33, Imberhorne Lane |

Mrs Bridgland |

25/03/1945 |

Slight |

P.P. |

|

George Brooker |

35, Imberhorne Lane |

Mrs Smith |

25/03/1945 |

Medium |

P.P. |

|

George Brooker |

37, Imberhorne Lane |

Mrs Webber |

25/03/1945 |

Slight |

P.P. |

|

George Brooker |

39, Imberhorne Lane |

Miss Heasman |

25/03/1945 |

Slight |

P.P. |

In 1953, the head of households of the twelve cottages in Imberhorne Lane were:

17: F H Hicks

19: William Bonny

21: James N Skinner and his wife Minnie

23: R H Murphy

25: J H Simmons

27: Dennis R Mason

29: Albert E Harnblow, husband of Barbara née Hewitt

31: Charles Baldwin and his wife Rose

33: Albert E Bridgland

35: Mary Strong, widow of Harry

37: Albert E Webber

39: Joan M Kuhagen

These were probably the last residents that lived in nos.17-39, Imberhorne Lane [odd numbers only] as the properties, like so many other dwellings in the local area, were subject to the terms set out in the Landlord and Tenants Act of 1954, aimed at ensuring tenanted dwellings were fit for modern, mid 20th century living.

Although no documentation has yet been found, the most likely scenario for the demise of the properties is that the landlord of the twelve cottages was either unable or unwilling to comply with the requirements of habitation fit for purpose as laid out in the 1954 Act. To be unable to comply with the requirements meant that the dwellings would have to be demolished and the residents re-housed. Thus, having stood empty for a short period of time, the twelve cottages were demolished circa 1958/9, being replaced by two blocks of council owned maisonettes – 17-47, Imberhorne Lane [odd numbers only]. The twelve cottages had stood for just over eighty-five years during which time they had been home to numerous hard working families, creating a settled community of people with interconnecting family ties on the east side of the north end of Imberhorne Lane, which extended across the road to the west side (further information follows in Lost Property of Felbridge, Pt. 3).

Bibliography

Handout, The Early History of Hedgecourt, JIC/SJC 11/11, FHWS

Handout, Charles Henry Gatty, SJC 11/03, FHWS

Handout, St John the Divine, Felbridge, SJC 07/02i, FHWS

Handout, Civil Parish of Felbridge, SJC 03/03, FHWS

East Grinstead Directory, 1928, FHA

Handout, Biographies from the Churchyard of St John the Divine, Pt.3, SJC 09/06, FHWS

Handout, Lost Property of Felbridge, Pt.1, JIC/SJC 07/18, FHWS

Tin Hut

Documented memories of past local Felbridge resident, AJW Jones, FHA

Handout, Memories of StreamPark and The Birches by A J W Jones, SJC 05/01, FHWS

O/S map 1938, FHA

O/S map 1955, FHA

O/S map 1979, FHA

Jones Photograph Album, FHA

A History of East Grinstead by M J Leppard

East Grinstead Directory, 1953, FHA

The Bungalow

East Grinstead Directory, 1953, FHA

O/S Map, 1936, FHA

O/S Map, 1955, FHA

Birth, Marriage and Death Index, www.freebmd.org.uk

Handout, Eating and Drinking establishments of Felbridge, Part I, SJC 05/07, FHWS

1939 Register, www.ancestry.co.uk

Martin Roper Family Tree, www.ancestry.co.uk

O/S map, 1962, FHA

North End Pumping Station

The History of East Grinstead by Wallace H Hills

O/S map 1879, FHA

Public Works Loan Commissioners Report, Sussex Agricultural Express, 20th February 1892, www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk

O/S map 1895, FHA

Public Works Loan Commissioners Report, Horsham, Petworth, Midhurst & Steyning Express, 10th December 1901, www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk

Housing of the Working Classes Committee Report, Sussex Agricultural Express, 9th August 1902, www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk

O/S map, 1910, FHA

Public works, Crawley & District Observer, 8th June 1940, www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk

O/S map, 1955, FHA

O/S map 1962, FHA

O/S map 1979, FHA

Jones Photograph Album, FHA

Documented memories of Felbridge resident, S J Clarke, FHA

Temporary Works of Sewage, local newspaper articles, 7th & 14th May 1956, EGTM

Handout, Memories of StreamPark and The Birches by A J W Jones, SJC 05/01, FHWS

Documented memories of former Felbridge resident, Nicholas J Jones, 2018, FHA

Public Lime Kiln

The History of East Grinstead by Wallace H Hills

Handout, Lime Kilns & Lime Burning in Felbridge, SJC 11/00, FHWS

6” O/S map, 1873, FHA

17, 19, 21, 23, 25, 27, 29, 31, 33, 35, 37 & 39, Imberhorne Lane (aka 1-12, Imberhorne Lane)

Census Records, 1871, 1881, 1891, 1901, 1911, www.ancestry.co.uk

O/S map, 1873, FHA

Auction details, Sussex Agricultural Express, 29th September 1888, www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk

Auction details, Surrey Gazette, 1st October 1889, www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk

Auction details, Sussex Agricultural Express, 19th October 1889, www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk

O/S map, 1895, FHA

O/S map, 1910, FHA

Imberhorne Lane postcard, c1920’s, FHA

Jupp Photograph Album, FHA

Jones Photograph Album, FHA

Handout, Pte. Sidney Godley VC, SC 03/00, FHWS

Handout, Lost Property of Felbridge, Pt.1, JIC/SJC 07/18, FHWS

Handout, Eating and Drinking Establishments, Pt. 1 SJC 05/07, FHWS

The Blounts of Imberhorne by J G Smith, pub. by the FHG

A Girl Called ‘Tom’, memories of Olive Sharman, pub. c1985, FHA

Dixon’s East Grinstead Directory, 1886, EGTM

Dixon’s East Grinstead Directory, 1914, EGTM

Dixon’s East Grinstead Directory, 1915, EGTM

Dixon’s East Grinstead Directory, 1916, EGTM

1939 Register, www.ancestry.co.uk

War Damage Reports, Ref: Add Mss 47855, WSRO

East Grinstead Directory, 1953, FHA

Documented memories of Tony and Marion Jones, FHA

Documented memories of Janet Wilkins, FHA

Documented memories of John Deane, FHA

Our thanks are extended to Janet Wilkins for all her help and information on the Hewett/Hewitt and Marden families.

Texts of all Handouts referred to in this document can be found on FHG website: www.felbridge.org.uk

JIC/SJC 07/19

Appendix Extract of the 1895 Ordnance Survey showing the revised property numbering